Introduction

(Introduction is optional. TL; DR this part for people who are in the process of understanding how ANS works, so you need to be familiar with ANS theory in some sort to be able to follow with this part)

While making a series of posts about entropy coding, it’s impossible not to mention ANS (Asymmetric Numeral System), an alternative method of encoding entropy proposed by Jarek Duda around 2009 (which was completed with the help of Jan Colet’s parallel work on FSE). Unlike AC and PPM, we have at least three detailed guides about how to implement it and why it works at all, from people like Charles Bloom, Fabian Giesen and Jan Colet, each of whom add their own code examples. If you’ve somewhere read or heard about ANS then there’s a ~98% chance you’ve seen links to their works.

Basically, their material gives you the opportunity to understand how rANS and FSE/tANS work at all, doing so still remains a challenging task, especially for people who decided to deal with rANS before classic AC (one of whom was I, since I had followed Fabian’s blog for a long time). Like an absolutely regular, adequate person, I was trying to find some alternative resources on Google. However, these small number of alternative explanations that I found were basically just a mixture of the original works but in a much shorter volume (except for a one maybe) and don’t answer any of the “why” question that I had. It can easily be the case that I am not their target audience, there are no questions. At the end, I ended up with that it would be much easier to continue digging into the works of people who make ANS theory work.

Although it is not hard to grasp the general idea behind how rANS and FSE/tANS works, but details of ”why” it works become not so obvious. These small pieces of puzzles, I always had the feeling that it’s something obvious, that it’s just in front of me, I need just to catch it, but I can’t because I don’t see it. After the 5th run of reading, I stopped counting but kept digging further because I understood that I would not find better material. I still think so. If you really want to understand how ANS works, you 100% need to read original works. So basically, I don’t see any sense in doing “another guide on rANS”. Instead, this article will be based on my notes where I make points about all these non-obvious things that I faced when I started to dig into rANS, FSE/tANS. This article is intended for people who have at least once run through the material that I have linked. Otherwise, everything written below will not bring much benefit, since I omit many things and use formula notation from the original article.

rANS

To have the ability to encode entropy with saving information about the fractional part, we need a buffer that will accumulate these fractions of bits, which essentially is our base. In the second part, where we look at AC, such buffer was low and high values that we imagine infinitely approach each other on x/p from MSB part. In the case of the rANS our buffer (base) will be just one integer that grows from LSB part.

You can imagine about how rANS works in two directions. The first is like the growth of the number by entropy, and the second is like the alternation of numbers in an asymmetric numeral system, which is the idea behind ANS. Although the second way is “canonical” it can be confusing, especially if you concentrate on a slot repetition cycle that takes a symbol (one of the best alternative explanation concentrates on this aspect, author is just much better at math than I am).

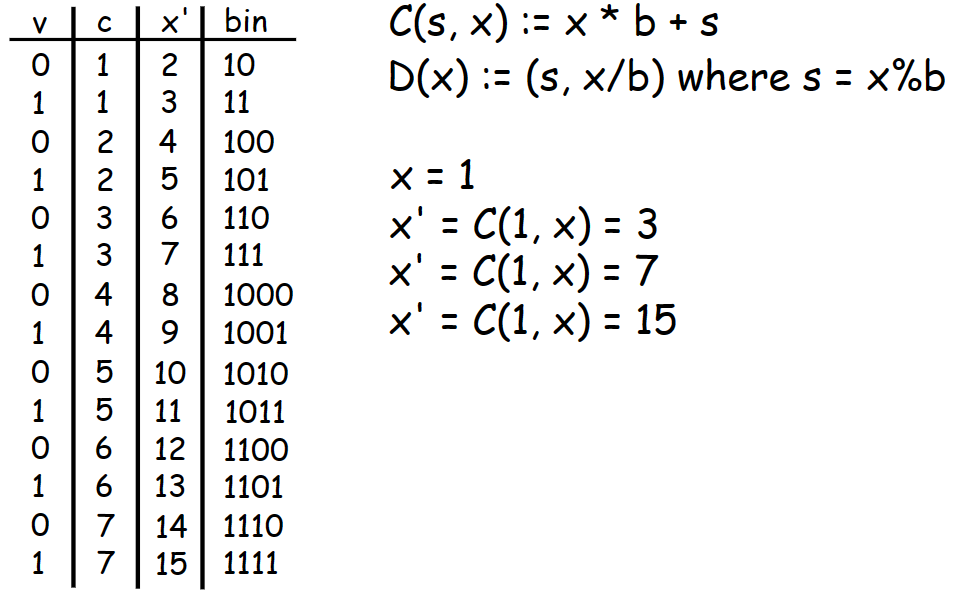

Let’s look at the simple example of encoding some values in one integer in base 2 where symbols have equal probability.

For base of 2 it is just shift plus bit to encode. The current state of the integer lies directly on the encoded bits, so it can be easily seen what was encoded in this integer. This example is very easy to understand but as you can see, we are already skipping some slot repetition cycle due to multiplication by base. In this case it intuitively understandable why this happened, though.

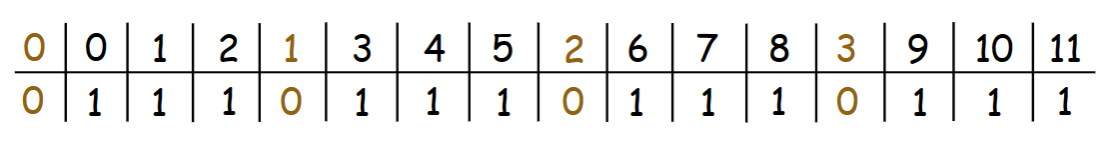

What If we want to encode symbols that have probabilities like 1/4 and 3/4. Their cycles should now conventionally look like this.

But as you already should know, rANS operates with states like this.

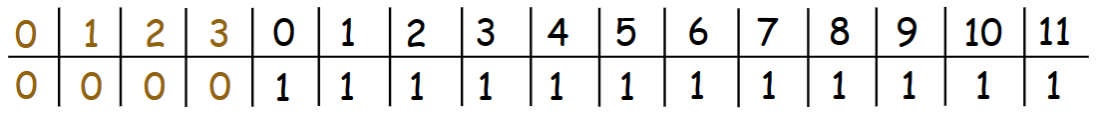

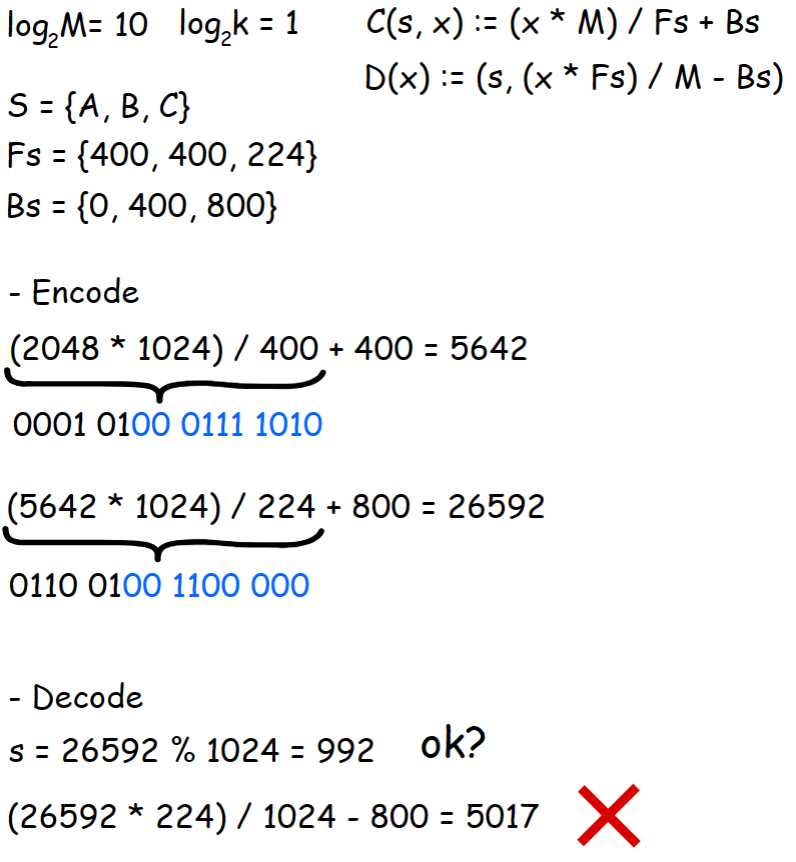

In order to account for symbols probabilities (e.g. it may not be a power of two), we need to change the formula. Now the increment of the number should be done like \(base * x\) where \(x = CDF[Total]/Fs\) (or \(base / x\) where \(x = Fs/CDF[Total]\) ). To make this at least somehow work, we must rearrange multiplication because we work with integers, as in the classic AC. For now, let’s write it like $(x*M)/Fs + Bs$, which in theory should give the most accurate increase. Adding Bs for distinguish encoded symbols.

I haven’t put any numerical representation for states in the last two pictures on purpose because what exactly should be there? We obviously need more space to have the ability to encode fraction of a bit. In addition, in this case, the more there will be a difference between a start value of a base and maximum value of CDF, the more precise the increase will be.

We can say that \(log_2(x) \;– \;log_2(M)\) is a k coefficient.

Of course, like in the case with AC we can’t think about encoding in isolation from decoding. Like in the example with encoding with base 2, for decoding, we need to do (x%M). The main difference now is the uneven growth of our base. In addition, at (x%M) for each symbol that we have, we get not just one value but rather a range of values between \([Bs, Bs+Fs)\). Both of these factors lead to the fact that by encoding a symbol like \((x*M)/Fs + Bs\), later at the decoding side \((x*Fs)/M \;–\; Bs\), we will not get to the right previous state of our base.

At each particular step of encoding, it may seems that after we take reciprocal, we get roughly right answer, but actually, we lose information about where we are in ANS automate. Adding (x%F) in this case also will not help because we shuffle bits of the base (and with it lower M bits) too much.

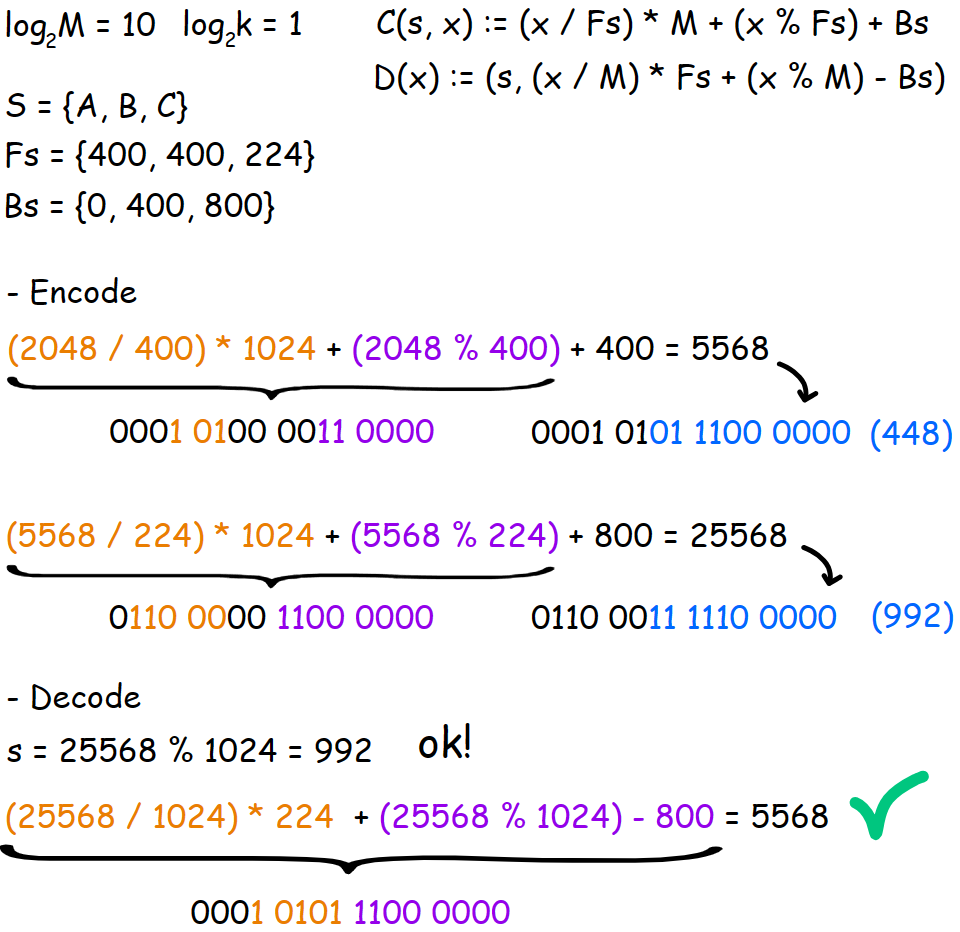

For doing decoding right, lower M bits must not be involved in the division. To avoid this, we are changing the process of encoding like this \((x\;/\;FS)*M \;+\; (x\;\%\;FS)\; +\; Bs\). The (x%FS) is our lost bits at the division, also without this information we will not be able to reach the right previous state at the decoding step.

During decoding we get the same value, but this time we actually are able to roll back the state. I highlight (x%M) – Bs at the decoding for a purpose because it is basically one operation that allows us to get (x%FS) fraction back, the value of which lies in the \([Bs; Bs + Fs)\) range. So, basically, operation (x%FS) allows us not only not to break an automate but also serves for carrying a fraction of bits to lower M bits.

So you may notice that by encoding symbol C first, for example, we have no choice but to increase our base at least by Bs of symbfol C. That is, during encoding, sometimes we will increase our fraction part more than we would like. Sound not very optimal, but it’s not that bad in practice. I took test files and encoded them as all their symbol were written sequentially. Despite the fact that the final entropy of the rANS state did differ, it actually did not differ much to make a difference in the final result. The final state may be different depending on the encoder parameters.

(rANS with 1 byte at a time normalization, table log2 = 12, L = 23 bits)

| name | orig. log2 | seq. log2 |

|---|---|---|

| book1 | 25.7156 | 25.0355 |

| geo | 30.1495 | 29.8343 |

| obj2 | 25.9816 | 25.5086 |

| pic | 27.8668 | 27.6645 |

The point being that this does not play a big role. The main losses happen due to several other reasons. The first one is normalization, since we conventionally build a large number each time we are doing normalization, by throwing off lower bits, we are getting slightly off. The second one is because we are doing an increment on the fractional part, not as precise as it can be.

FSE/tANS

For me, one of the non-obvious things was why we always end up in the state that we actually need at encoding/decoding? Let’s look at a simple example with encoding a symbol that have a power of two probability.

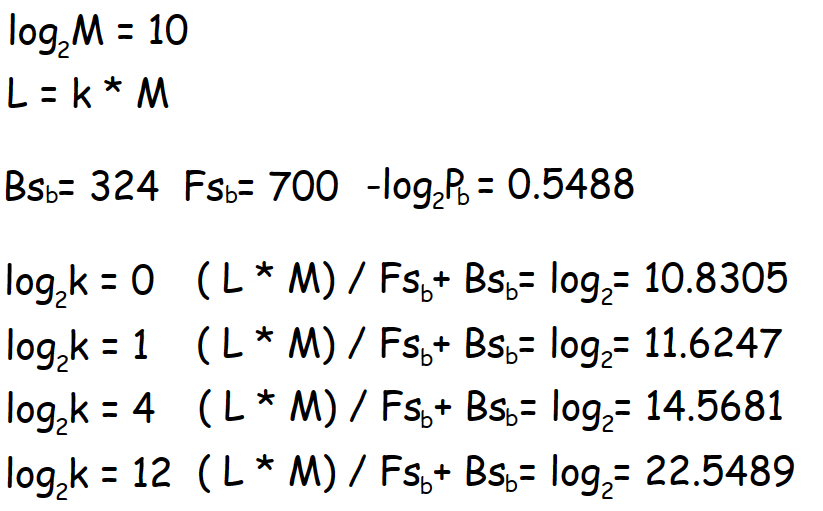

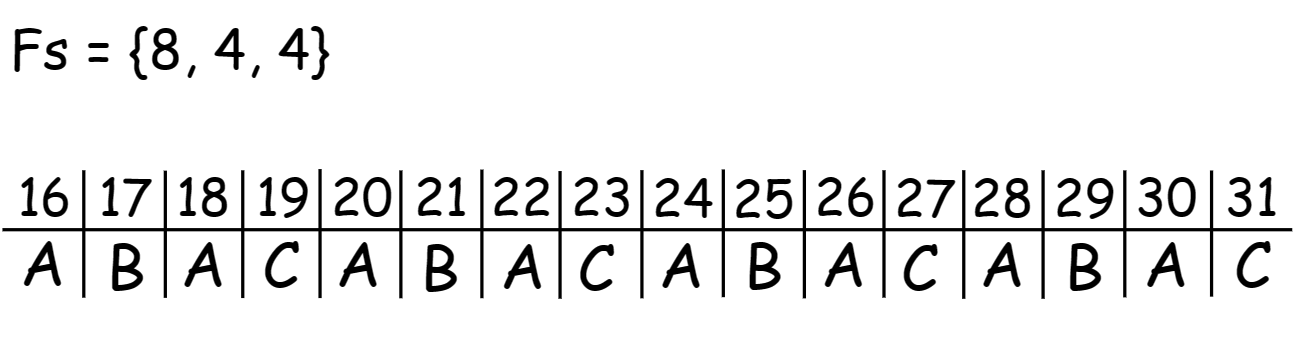

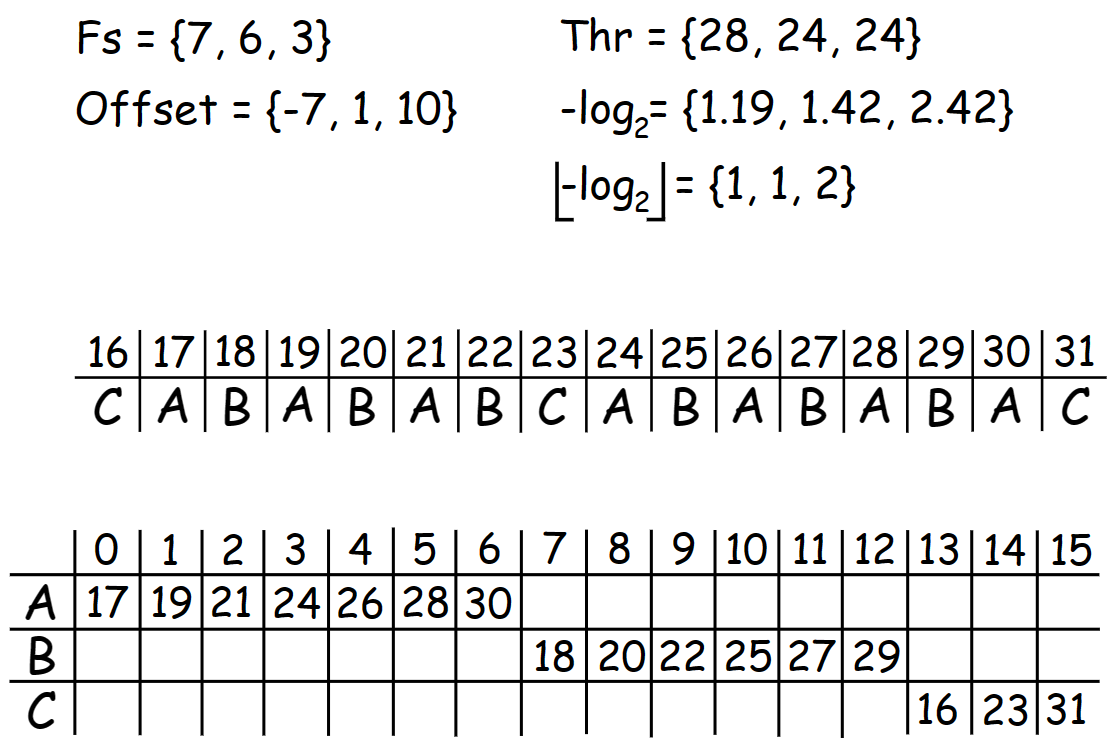

Although the table looks like this

But what we actually storing in memory is something like this.

Symbols B and C have the same valid coding interval [Fs, 2Fs-1], i.e., after normalization, from any state, we get the same value for both of them. However, depending on the symbol we choose, the offset that belongs to this symbol gets us to the proper state. For example, let’s start from state 16. We throw away 2 LSB and get 4. Then, depending on the symbol B or C we get to state 17 or 19.

In the example above, if you try to encode the same symbol several times in a row, you end up staying in the same state since neither of these symbols has a fractional part that it should carry to the buffer. Unlike in the example bellow.

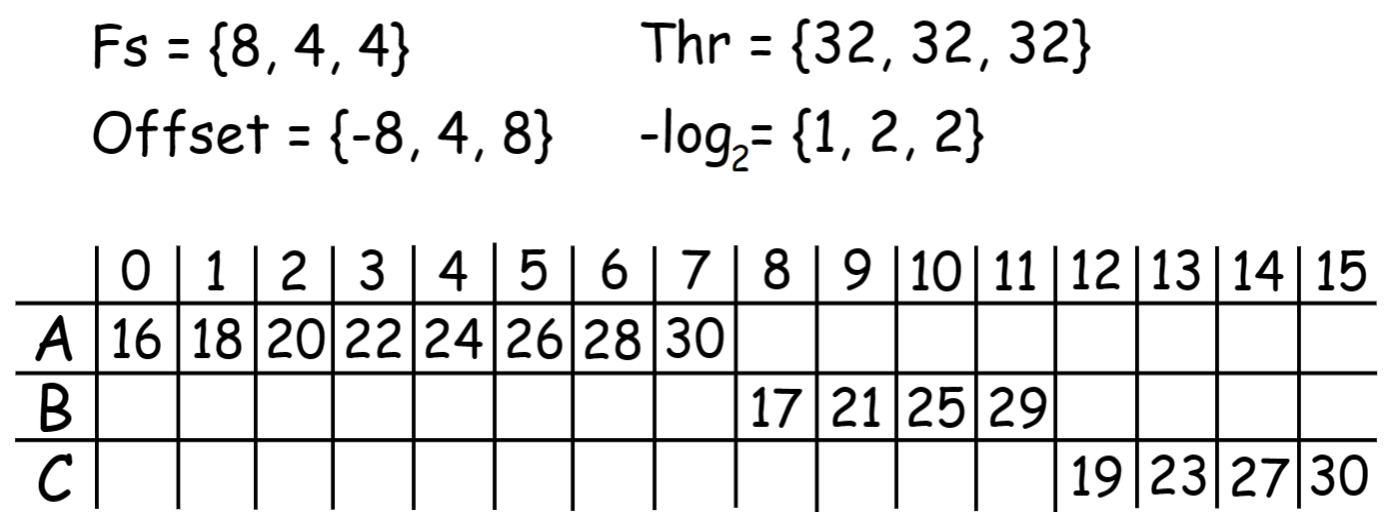

This look more like something real. Now, if we keep encoding symbol A, even though we write one bit, the base will change by \(log_2(19)\; – \;log_2(16) = 0.25\) bits (if the base had more resolution, then precisions would be higher, of course). Also, this time we actually need the Thr value because now it tell as when we need to output n + 1 bits for current symbol so we can stay in the [Fs, 2Fs-1] range affter normalization. By the way, as you can see, value of Thr can match, since in this case, \(-log_2(B)\) and \(-log_2(С)\) have the same fractional part.

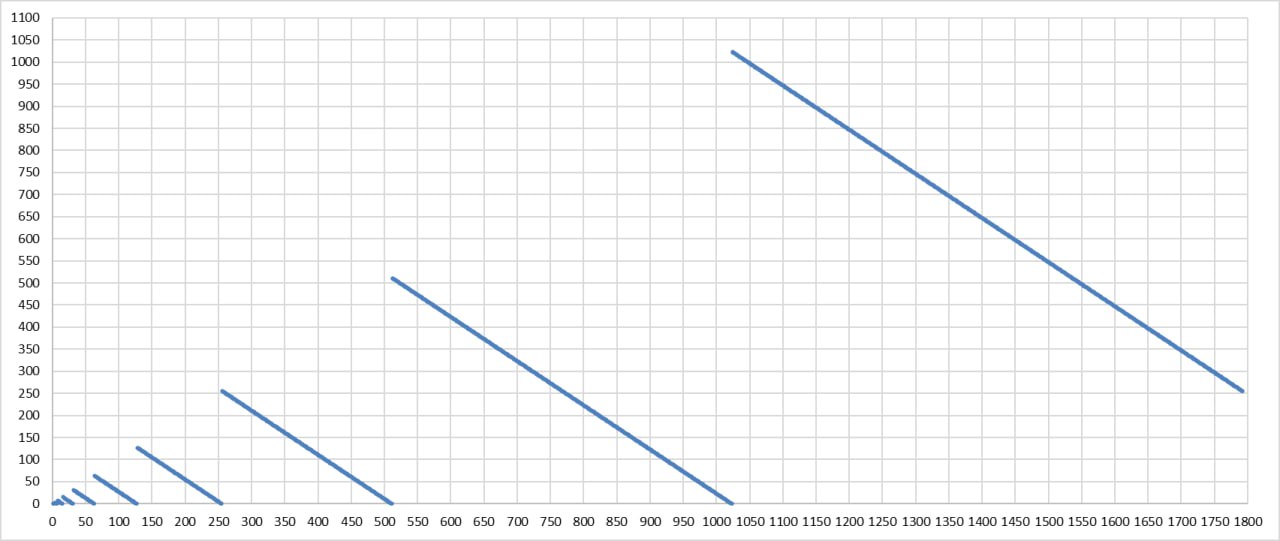

At first, since we lowering our base by n + 1 bits instead of n bits, it may seems that we decrease the count of available state for symbol to witch we can jump by a factor of 2, but it’s not true. It is all depends on the fraction of bits that the symbol has. Below, the graph shows the frequency of the symbol in x-axis and the maximum number of states it can reach after normalization in y-axis (L = 2048).

In this way, a symbol with a frequency of $-log_2(1025/2048) = 0.9986$ very rarely needs 0 bits, so it will write n + 1 bits for most of its code space. A symbol with a frequency of $-log_2(1023/2048)= 1.0014$ almost never needs 2 bits, and after normalization, it only goes into an n-bit slot.

Why [Fs, 2Fs-1] for FSE/tANS?

Some may notice that for rANS [Fs, 2Fs-1] would mean that we can normalize only one bit at a time. So why with tANS we read/write as many as we need? Or why with rANS we can’t read/write as many as we need? Besides the fact that working with 2^n bits, you can, in theory, simplify your bits IO, we remember that you can’t think about the encoder without the decoder and vice versa. For making streaming ANS work, we need to know when we need to throw off or get bits exactly. One of the main features of the ANS is precisely the fact that we know in advance our normalizing interval, unlike in the classic AC. This is possible thanks to the b-uniqueness property and the satisfaction of the properties that bring up with it, which guarantee that the encoder and decoder cannot have two valid states:

\[\begin{flalign} &L = kM;&\\ &I = [L:bL);&\\ &I_s = \{x|C(s, x) ∈ I\};& \end{flalign}\]Let’s imagine what is going to happen if we would write only as many bits at the rANS normalization stage as the symbol requires. If during the encoding of symbol s, we’ve thrown off 5 bits to let it stay in a valid range, then at decoding, before doing the (x%M) operation for symbol s - 1, we need at first normalize the state back to as it was before encoding symbol s, but we don’t know exactly how many bits we need to read, we are know that we just below the value of L (we in theory know that the symbol take from n to n + 1 bits, though). If we start reading bits one by one, then we may think that L + 1 is a valid state, but if the state from which we’ve made normalization actually was L + 2, then that’s the end of the story. So, to keep the encoder and decoder in sync we need to read and write same amount of bits at the same time. Because of the fact that we don’t know precise properties of each state, we tweak b, k and M properties to adjust such parameters as:

- Coding resolution

- How often we are doing normalization

- How many bits of normalization are required

But as you may already guess, if we had more information about each state, then we could be more flexible in terms of normalization at encoding and decoding. So in the previous situation, as long as we know exactly from which place in the table the symbol s got to state x and how much the encoder recorded from this state, we can accurately obtain the previous state for the symbol s - 1.

ANS in real word

Is the ANS useful at practice? Of course! Two fastest LZ codec use them for their needs, zstd which can be said already become a standard choice, and Oodle licenses of which were purchased for use in PS5 and Unreal Engine. Dropbox also experimented with ANS by stacking multiple contexts for CDF blending, but I’m not sure if they really use it internally.